Last week, we learned from Kathleen Sciacca, a pioneer in the development of integrated treatment for co-occurring mental illness and substance disorders, that “Motivational Interviewing (MI) is grounded in Carl Rogers’ “client-centered” counseling and “empathic reflective listening.”

This week, we are fortunate to have another opportunity to learn more about this client-centered approach with Kathleen

So without further ado, Kathleen, what role does Prochaska and DiClemente’s Stages of Change Model play within the model of motivational interviewing (MI)? Is it sort of a gauge as to when/how you would employ the various motivational interviewing techniques?

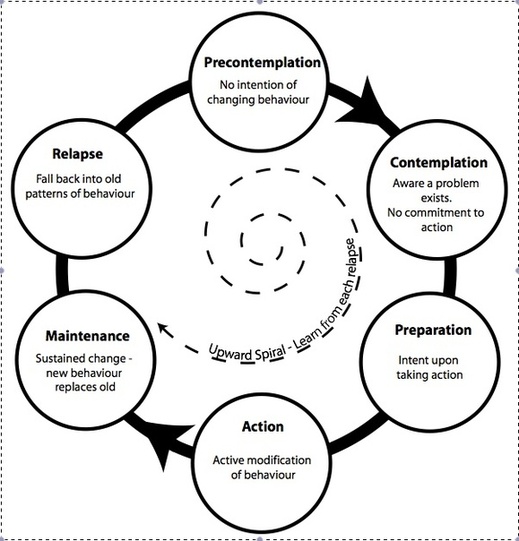

In the original book on MI (1991), the authors embraced Prochaska and DiClemente’s stages of change (SOC) and integrated their interventions with the SOC. As time went on, providers did not experience the SOC and MI as two separate distinct models which they are; this became a concern and it was declared that the SOC are not MI and need not be a part of MI.

The SOC have very strong merits when it comes to practicing interventions. One thing that both MI and SOC agree upon is that the intervention must be one that the client is willing/able to accept. If the provider is intervening at a readiness stage that differs from the client’s readiness to change or to accept the intervention it will engender discord, defensiveness or withdrawal and will not lead to change.

I have written extensively about the positive elements of SOC in a number of chapters/articles and most recently in the “New language for integrated care” article. One element that the two models have in common is that one can begin working with a client regardless of the client’s stage of readiness to change. SOC holds that change is incremental. They have done a masterful job of delineating the transition through stages people go through before reaching the “plan.”

Stages of Change reference: Prochaska, J.O., DiClemente, C.C. & Norcross, J.C. In Search of How People Change: Applications to Addictive Behaviors. American Psychologist, September 1992; Vol. 47(9) 1102-1114.

The fourth process in MI, is planning. It is followed in the SOC by going into the action stage with elements of the plan. MI interventions work well in the various stages. It is a collaborative respectful communication style that takes the client’s goals, perceptions and ideas into account as do the SOC.

The SOC are indispensable when it comes to working with multiple behaviors and symptoms. Clients are frequently at different stages of readiness to address different symptoms. The SOC can revolutionize how we assess and record client outcome. Whereby only clients in action have been considered successful outcome, each increment across the SOC change is progress and in many cases is over-looked; this can be detrimental to clients.

For example, there may be more than one provider who addresses a client from the perspective of a different stage of readiness. Or the client with multiple symptoms and behaviors may be at different stages of readiness to change or address different symptoms or behaviors. MI does not address multiple symptoms, behaviors or disorders. It is studied around specific, individual change areas rather than multiple ones.

Here is where it is very important that providers have a language for client readiness or readiness scales such as the ones I developed for co-occurring disorders. In the example I gave earlier, the client may be in pre-contemplation regarding alcohol, action regarding getting off probation and out of the criminal justice system; and contemplation regarding domestic violence – ambivalent. MI defines itself as a model that assists clients to resolve ambivalence – that is a direct correlate to the SOC contemplation stage – and where a pre-contemplator will be headed if he or she identifies reasons to change or change talk.

Kathleen describes change talk is in this video clip

Still thinking about the Stages of Change Model, how would you employ motivational interviewing in order to help a client take action?

For a client to move from pre-contemplation to contemplation, it requires that he or she identify negative elements of the target behavior in his or her life.

The provider needs to listen carefully for even the weakest change talk. “My wife doesn’t like my drinking.” Provider: “so it seems your relationship with your wife is affected by your drinking.”

A person in pre-contemplation will usually identify what I refer to as “peripheral problems” regarding the behavior rather than problems with the behavior itself. The provider may employ a SOC intervention known as the decision balance. Here the client might be asked to consider what is

good about staying the same and not so good about it. What is good about changing or not so good about it. The strategy is to elicit from the client reasons to change and reasons why not changing could be a problem. Once a client has identified negatives in relationship to the behavior he or she has moved to the contemplation stage.

Contemplation is marked by ambivalence – the client recognizes both positives and negatives but is stuck. Now the client feels both ways and is unsure about what to do. Here is where the “evoking” elements and the directional properties of MI would come into stronger focus. One wants to minimize attending to sustain talk – sustain talk is reason(s) not to change; and evoke, reinforce and strengthen change talk. When the client has identified more reasons to change or has strengthened his or her determination to make the change he or she may then decide to change. Empathic, reflective listening can deepen this process.

This would be followed by preparation or the “plan.” This is also a collaborative process. What does the client think may work toward effectuating this change. The provider asks permission to make his or her suggestions as well. The client and provider collaborate on a potential plan that is acceptable to both. The plan is flexible in that it can be revised as the client sees fit. There should not be anything in the plan that the client does not want to do.

The plan should optimize success and minimize failure. In the planning stage I recommend that a functional analysis be worked up with the client to find out what the triggers are regarding the target behavior and building in the acquisition of coping skills around those triggers as part of the plan.

As the client moves from preparation to action, the element of “confidence building” will be employed. One begins with the action that the client believes he or she is most likely to succeed with. Additional actions from the plan are employed at a pace that will most likely assure success.

As the client implements the plan into action and the target behavior goes into remission, the client is in action. The provider needs to maintain the same degree of support and direction in the action stage as in all the other stages; this is not a time to back off.

The maintenance plan (relapse prevention) should begin while the client is in action particularly if your work with the client is coming to a close. Just as there is collaboration, agreement and flexibility in the action plan there should be the same approach to the maintenance plan.

The client should have the opportunity to make some adjustments to the maintenance plan while they still have your support. If the client adjusts to the maintenance plan and it prevents relapse then he or she may permanently exit the stages of change. If the client “relapses,” this is not considered treatment failure, there are no punitive or negative consequences.

What it means is that something went wrong with the maintenance plan. We may have left something out; the client may have new people, situations in his or her life that we did not account for; the client did not follow through with part of the plan, etc. The approach is to revise the plan and get back to action and maintenance. However, once the client re-enters the stages he or she may be at any one of the SOC stages and one would need to intervene from that stage.

Are there any books/articles that you would recommend to readers interested in learning about motivational interviewing?

First, one must understand Roger’s work and the direct and indirect influence it has on MI. I recommend Carl Rogers and Carl Rogers – Wikipedia; it provides a good integration across the span of Rogers’ work.

Second, I recommend: “Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior” by W.R. Miller & S. Rollnick. I acquired my own foundation in MI from this book.

There is also a “free” TIP #35 available from SAMHSA. Although there have been changes over the years, the basic elements of MI are consistent and well grounded in the MI book.

Lastly, a more recent article that I found to be specific and well rounded is: Toward a Theory of Motivational Interviewing by William R. Miller and Gary S. Rose.

I understand that you provide a motivational interviewing training seminar. Could you provide a brief description of it and tell us how it differs from others offered?

When I sponsor an MI training seminar myself, I have the luxury of designing a three-day course that allows me to provide the extent and depth of information I prefer. This enables some grounding in the theory and practice of MI, the SOC and some compatible cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) interventions.

I have time to include live demonstrations, early practice, and discussions to follow all areas of training. There is ample opportunity for experiential practice that becomes more advanced incrementally and results in the practice of MI sessions with real situations and not role-play.

The key to learning MI is to practice. Practice with your own “real play” rather than role-play. The provider can personally experience what the interventions feel like, where they take them and whether or not they are worthy of continued practice that requires self-discipline.

I make an effort to remain current with MI’s transitions and nuances. I can respond to questions that pertain to many case examples presented by participants from a variety of disciplines; I have a wealth of examples from my own practice and my work as a consultant, trainer, educator and program developer.

Lastly, aside from taking a course in motivational interviewing, what other career advice would you offer to mental health professionals who are looking to develop their motivational interviewing skills?

First, would be to develop a “client-centered” communication style to be integrated with whatever model of intervention one uses or prefers. As Roger has eloquently described, this is a “way of being with people.” The client-centered approach is a respectful, collaborative, empathic communication style that is necessary for building a trusting relationship where clients are free to communicate.

Next, would be to practice being present – staying with the person – listening carefully – conveying your understanding of the client’s thoughts, perceptions in a “non-judgmental” manner, following.

Learning to elicit from the client rather than “telling” him or her what to do. Always ask the client’s permission to give advice, education, suggestions and ask for feedback after you have done so -collaborate.

Then it will be worthwhile to learn reflective listening and to discipline oneself to practice it. This is a potent skill that can serve ones practice very well throughout ones career.

Thanks so much, Kathleen, for taking the time to share some of your expertise on motivational interviewing with us !

You may follow Kathleen on twitter at @DualDiagCoOccur

What questions/comments come to your mind about motivational interviewing? What are your thoughts about employing such an approach in your agency/practice?

You May Also Enjoy These Links from Kathleen:

Dual Diagnosis

Motivational Interviewing Clips in Primary Health

Motivational Interviewing articles, fact sheets and more

Additional Motivational Interviewing articles

Motivational Interviewing Training Seminar