Growing Together by Nancy-Lee Mauger

Growing Together by Nancy-Lee Mauger

This artwork exhibits 25 parts of the artist;

Shy (26th) chose to remain hidden.

Would you be able to correctly diagnose an individual with Dissociation Identity Disorder (DID)? Between 1-3% of the general population have this mental illness, but only about 6% of them actually present with visibly distinct alternate identities.

As a result, many mental health professionals misdiagnose individuals with DID based upon the combination of symptoms they happen to present with simultaneously such as depression, panic attacks and substance abuse.

To help us get a better understanding of this disorder, Social Work Career Development sought out the expertise of Tom Cloyd who has an MS in Counseling Psychology and an MA in Cultural Anthropology); he specializes in research on trauma and dissociative disorders.

Among Tom Cloyd’s achievements in the field, he is the founder/moderator of the EMDR Resource Cooperative Internet Discussion List (for professionals), and the Google+ Trauma and Dissociation Education and Advocacy Community and website.

Without further ado, Tom, could you share with us a bit of your background? What led you to move from psychology [and anthropology] to specialize on trauma and dissociation identity disorder?

I was originally training for a research and teaching career in cultural anthropology, but after passing my Ph.D. qualifying exams I realized I didn’t want this. I left graduate school and was for a time a professional ceramic artist. Both of these endeavors deeply satisfied a part of me, but not all. I then decided to act on an interest I’d had for years, took a number of psychology courses, and was admitted to a top-10 graduate program in Counseling Psychology.

It was an excellent training experience, but again I found that I had little interest in pursuing a PhD, and so returned to my home in the Pacific Northwest, now with two Masters degrees. I’ve always been self-directed and independent, and I was ready to strike out on my own.

Hired as Director of Admissions at the major psychiatric hospital in Portland, I had a valuable, unintended internship in serious mental illness, and after two years was more than ready for full time clinical work. Hired as Program Manager of the northern branch of a county mental health clinic in rural eastern Washington. I soon learned that my training was inadequate. I could see that psychological trauma, plentiful in my case load, was not being well handled by anyone in our 80-person staff, including me.

I got trained in EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing), and suddenly everything changed: I started actually curing people, usually rather quickly. When it was clear that my agency was not able to adjust its clinical program to fully take advantage of this breakthrough treatment protocol, I resigned and went into private practice. I’ve been a trauma specialist ever since.

Trauma work tends to center on Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), but it also brought me into contact with Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID), which clearly is primarily a trauma-response disorder. Both are complex and demanding, as well as under-diagnosed and therefore under-treated. We have a great deal of work to do in educating the public about both disorders and what we can do with them, and to that and my clinical work and research I have dedicated the rest of my professional life.

How would you define “dissociation?”

Dissociation is quality of the mind which, by itself, does not necessarily indicate a need for professional intervention. However, when any of a number of specific other symptoms are also present, an individual may meet the criteria for either a DSM-5 Trauma- or Stressor-Related Disorder, and/or a Dissociative Disorder. It is possible to have both. Virtually all people with DID also have PTSD, for example.

“Dissociation” is a confusing term, because in psychopathology it can refer to at least three distinct problems. The most common usage refers to a condition of expression, or consciousness. The less common refers to a quality of personality structure.

Remarkably, the first sentence of the detailed definition of dissociation given in the DSM-5, which talks of “…the splitting off of clusters of mental constructs from conscious awareness…”, is an excellent neuropsychological description which encompasses all three problems.

The first dissociative problem is one of the “negative symptoms” that is seen in people with schizophrenia – “negative” meaning that something one normally expects to see in a person is distinctly not present. In schizophrenia, this may be seen as an apparent separation of ideas from feeling usually associated with them – a kind of expressive detachment.

The second problem that can be called “dissociation” is a condition of consciousness – a quality of the mind in which there is a separation (partial or complete) of clusters of information in the brain. This separation is a significant departure from the brain’s “…normal integration of consciousness, memory, identity, emotion, perception, body representation, motor control, and behavior”, and can occur in a variety of ways.

One of the more commonly seen, we can easily recognize as “spaciness” – when a person is physically present but seems to have their attention placed elsewhere. Less common, and more striking, is the distinctly separate identities seen in the mind of person with DID.

The third use of “dissociation” refers to a developmental problem which is said to arise when a child is subjected to severe and/or chronic stress. This new idea in the professional DID treatment community was actually described well over 100 years ago.

Referred to as “structural dissociation,” it builds on the work of one of the leading dissociation researchers, Frank Putnam, who has written about the normally seen emergence of “discrete behavioral states” in children. As he describes it, children are born with about a half dozen such discrete behavioral states already in place in the brain. With time and environmental interaction, additional states develop.

Shattered Mirror, Shattered Me

by Laura Alisha Myers-Doughty

What exactly is Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID)?

Initially, the discrete behavioral states typical of early childhood are not well connected (integrated), so transitions between states are primitive and discontinuous. With normal maturation, a significant degree of integration between these states will occur. However, this developmental integration does not necessarily occur under conditions of extreme and/or chronic neglect or neglect.

With such stress present, we may well see a developmentally stalled organization of the self, a pathology whose key feature is a personality split into functionally dissociated parts – the classic major symptom of Dissociative Identity Disorder. These parts need not be totally separated. Such partially separated parts of self are also seen in the other trauma disorders, such as when someone with Acute Stress Disorder, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder or Complex PTSD experiences a “memory intrusion.”

Dissociative Identity Disorder is a formally designated mental illness, and has been since 1980 (termed “Multiple Personality Disorder” at that time). Since 1980, the key feature of all the dissociative disorders has been disruption of the normal connectedness of identity, memory, etc. This has not changed, through the DSM-IV and on to the DSM-5.

The criteria for a diagnosis of DID itself requires a divided sense of self, distinct and serious disruption of memory, impact upon one’s life in one or more major areas of functioning which cases significant distress, and that these symptoms cannot be accounted for by the assumption of cultural roles (a bit tricky to explain) or by the effects of substances or medical conditions (a standard DSM “rule-out”).

A very commonly encountered error is to take the DSM diagnostic criteria as a description of DID. They categorically are not. Diagnostic criteria are what one must see to make a diagnosis, and nothing more. Psychologist Paul Dell (2006) has done research which clearly demonstrates that MOST of the distinguishing features of DID are not known either to those with DID, or the vast majority of psychotherapists, much less the general public. They are also very inconspicuous. These are aspects of people with DID which simply do not occur in people who do not have DID, and only a small number of them are seen in the DSM diagnostic criteria.

How is Dissociative Identity Disorder related to childhood trauma?

There are two essential things to understand about the relationship between childhood trauma and DID. FIRST, all trauma is, by definition, an overwhelming experience. While it is commonly talked about in terms of external events, not subjective experience, this is very misleading.

If when discussing trauma we look only at events, we miss the fact that it is not what has happened to someone that is traumatic but how the individual reacted to it. As a clinician, this is painfully obvious to me. That reaction is ongoing, and that is what brings them to my office.

As psychiatrist Daniel Siegel puts it, “At times the mind cannot organize itself effectively in response to experiences. Such experiences are traumatizing, in that they overwhelm the brain’s ability to adapt.” In this view, something is traumatic because of the feelings it provokes, and it is those feelings which overwhelm, not the event.

Because the sudden burst of feeling (and we’re always talking about FEAR), dominates the brain at the moment it is produced, it necessarily disrupts one’s normal sense of self. A separate, fear-saturated state is produced. If one is able to assimilate that state fairly quickly, there is no lasting problem. If not, we have psychological trauma.

Children have distinctly limited ability to assimilate overwhelming experience; in this sense they are unusually vulnerable. If what must be assimilated is too overwhelming, and especially if this comes at the child’s brain repeatedly and fairly constantly, we get a state of chronic overwhelmedness, due to an inability to “digest” life experience. This can be seriously damaging, in a number of ways.

The DMS-5 puts it plainly: DID “…is associated with overwhelming experiences, traumatic events, and/or abuse occurring in childhood.” In addition, psychotherapist Elizabeth Howell points out that emotionally overwhelming experiences not uncommonly occurs to children at the hands both of family and non-family members. She specifically mentions medical trauma, especially coupled with parental abandonment at hospitals. (It should be noted that DID is NOT associated with trauma occurring outside of childhood.)

The SECOND thing to know about childhood trauma and is DID is that, for many reasons, we cannot yet say categorically that trauma is always involved in DID. Controlled observational or experimental studies of the development of DID are nonexistent. It is ethically unimaginable to consider doing such studies. Because in the cases we do have any idea at all about causality early childhood trauma is always a key feature, and early childhood memory is usually sketchy at best, we’ll never have data on the development of this disorder that even approaches the quality of data routinely seen, say in adult onset PTSD. So, we can reasonably account for a majority of, but not all, DID cases, and overt trauma cannot always linked to it.

Still, psychological trauma is clearly the major causal issue. Researcher Bethany Brand, in a recent and ongoing naturalistic international community sample of 280 Dissociative Disorder patients (the overwhelming number of which may be assumed to have DID), found that 79% reported physical abuse as a child, 86% reported sexual abuse as a child, and 94% reported emotional or psychological abuse as a child. It is likely that these rates under-report actual incidence of these abuses, because early childhood memory is involved.

I should mention another factor related to trauma and dissociation in childhood: attachment failure. If we accept the idea that secure childhood attachment (to a parent) is a critical factor for development of a normally functioning adult personality, what happens when this critical factor is not present? Many trauma therapists will tell you (I among them) that their most disturbed clients are not abuse victims but neglect victims.

For example, I was told once by a Toronto child psychiatrist that to be truly alone was the most terrifying thing that could happen to a young child. I have come to agree with her. My perspective on this is that attachment pathology is likely traumatic in at least some cases, and that disorganized attachment in early childhood is almost surely traumatic in itself. If we include grave attachment disorders in the class of chronic traumatic experiences a child can have, then there appear to be no data-supported OR hypothesized causes of DID which are not traumatic in nature.

Watching by Nancy-Lee Mauger

How do dissociation and/or repression enable a child and/or adult to forget their traumatic memories for 10, 20, 30 or more years?

“Repression” is usually described as “a defense mechanism”, involving forgetting or losing awareness of “unacceptable ideas or impulses”. The concept was central to Freud’s theory of the essential conflict between the individual and society. However, it’s an archaic term, used now mainly by a small minority in the psychotherapy community who still accept Freud as central to their thinking.

Forgetting, or difficulty in recall, is a common and well-documented phenomenon, and it occurs for a number of reasons, as do errors in recall. None of these phenomena are necessarily “a defense mechanism”. To automatically label as “defensive repression” an active avoidance of painful memory, or problems in recall due to extremely infrequent access of the material, or due to dissociation at the time of trauma, is just not helpful.

In addition, “repression” is confusingly related to, if not identical with, dissociation – depending on who you read in psychology literature. The problem with that is that dissociation is NOT forgetting, so this confusion is not helpful. If we abandon Freudian neurosis theory, and most of us have, we no longer need “repression” as an idea. We just need to examine problems with memory.

While we don’t yet have a good evidence base for accounting for memory problems in people with dissociative symptoms, the consensus of informed opinion is that normal integration of memory and sense of self can be significantly disrupted by the intrusion of physical/sexual abuse and neglect during childhood development, as well as by parenting styles that do not result in secure attachment.

This results not in a “forgetting” process but rather in the failure to create a normal integrated memory in the first place, and repression has nothing to do with it. It’s not even properly about dissociation, if we understand that to be alterations in normal consciousness, as I previously discussed. In addition to these considerations, we have the issues of adaptive avoidance of both recall and report, common in children living in hostile or hurtful families, also not “forgetting.”

The structural dissociation model of response to traumatic experience offers an intriguing alternative cause of memory problems. It proposes that in all the trauma-related disorders, from Acute Stress Disorder to DID, the experience of the traumatic stress necessarily causes a splitting off of awareness, such that memory of the experience is variably isolated from one’s normal sense of self, from the very beginning. After that, the problem is integration. If integration happens, access to the memory will be normal, although a mental disorder may still develop. If event memory integration does not occur, development of a pathological disorder is likely.

Another consideration that I’ll just touch upon is the question of the sort of memory involved. Narrative, story-telling memory is only created in brains of sufficient maturity. Younger brains will create primarily non-recallable “implicit” memory, and this has nothing to do with trauma. There will appear to be NO memory of an event, yet aspects of the event can still trigger serious emotional disturbances, if the event was traumatic. I have treated a number of people with this problem. Initially, they all thought they were “crazy”. We now have a superb, neuropsychologically based, treatment model for these sorts of problems, I’m happy to say.

So, I have to urge that this whole issue of memory and forgetting is both far from simple or adequately understood at this time. Theoretical repression or dissociation models of memory failure don’t begin to account for what we actually see in the real world.

Paradoxically, the problem with trauma disorders is NOT so much excessive forgetting, but excessive remembering. If real and substantial forgetting occurred, there would be no evident disruption of function and hence no disorder.

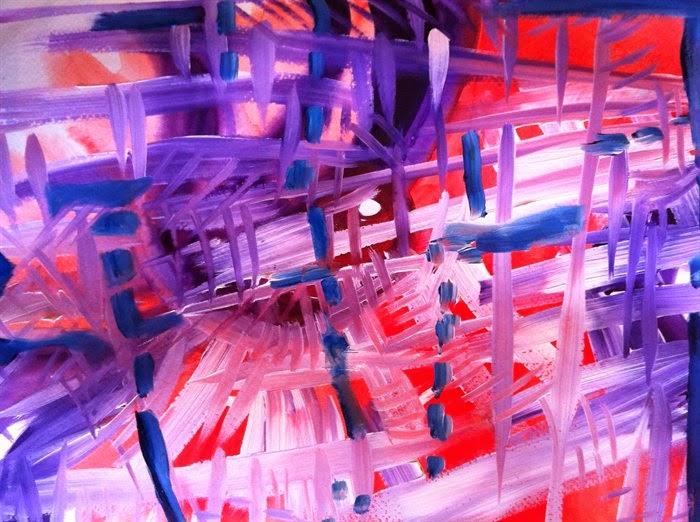

Hidden Chaos by Nancy-Lee Mauger

There is some controversy in the field regarding the authenticity of recovered traumatic memories [particularly if they have been accessed via suggestive hypnosis]. Assuming that no hypnosis and/or any “suggestive” techniques are employed, how authentic and/or reliable are the [formerly repressed] memories of survivors of complex traumas?

It’s amusing and annoying to see how often some journalist or other non-professional discovers that memory is not a video recorder. There are also well-known experimental psychologists who routinely draw a crowd by recounting in a sensationalizing manner the unreliability of human memory. This continues to happen simply because our culture in general persists in thinking that memory DOES just record what happened, when that is simply not the case. The truth is far more complex, so this issue is not likely to become settled in the common mind any time soon.

Just as in the courtroom, it is possible to “lead the witness” in psychotherapy. While at one time, there may have been problems of this sort, for quite some time now it has been part of the training of all psychotherapists to make a point of retaining a neutral position concerning events of a client’s history. We have neither the resources nor the training to engage in memory corroboration. Ross and Halpern have written an excellent and invaluable statement about how to manage client reports of abusive and traumatic personal histories, which I highly recommend. The issue of illicit influence of client memory by therapists had a brief life span, but has been essentially absent for at least the last decade. References to some alleged “controversy” continue to occur, however.

Let’s agree that memory, including that of psychological trauma, can be either continuous (uninterrupted) or apparently forgotten and later recalled (“recovered”). Chu points out that such “later-recalled” memories are a frequent reason for entry into psychotherapy, as well as a common occurrence in therapy. There have been several studies of the accuracy of such memories. They “…can often be corroborated and are no more likely to be confabulated than are continuous memories.”

So, where’s the “controversy?” The fact is that memory can be either very accurate or not, and can touch all points in between. People’s memory can be influenced by many things, including other people and the circumstances of recall. All this is well documented in the research literature. But psychotherapy is not about memory validation. It is about dealing with disturbances in the mind. We, therapists, need to stay focused on our job.

I know of a fascinating account that illustrates this perfectly. A man who had nightmares for years concerning his experiences in a WWII German concentration camp presented himself for therapy at the office of a trauma therapist. His disturbance was obvious and very real. There was, however, a small problem: he was born in 1949. The therapist was smart enough to know what her job was, and simply commenced trauma therapy.

As it progressed, the man recalled more and more (this is usually the case), including the fact that he’d grown up in Israel, in a house shared with his uncle, who used to tell stories around the kitchen table about his concentration camp experiences. The psychotherapy client was 5 at the time. Later, he forgot the story telling, but not the horrific stories. Not until his supposed “memories” were processed (de-sensitized) in therapy did he realize what had happened in his brain. His therapy was successful, and his intrusive flashbacks of events that never happened to him, but did happen nevertheless, ceased.

Thanks so much, Tom, for this informative introduction to dissociation and DID.

You may visit Tom at his website .

Did you enjoy this post? If yes, would you please “like” and/or share it with others? Thanks!

What questions/comments come to your mind about this introduction to dissociation and DID?

Nancy-Lee Mauger

Growing Together

Watching

Hidden Chaos

About the artist: Nancy-Lee Mauger is a 50 yr old woman diagnosed with DID in 2010. She uses art on a daily basis to help her navigate and cope with her mental illness. To see and/or purchase her art, you may contact her through https://www.facebook.com/NLMauger or paintingsilove.com.

Laura Alisha Myers-Doughty

Shattered Mirror, Shattered Me

About the artist: For Laura Alisha, art and writing are an integral part of daily life. She is self taught in many different mediums. “Without art, I can not live. Creating art, crafting, creativity, these are like breathing for all the parts of who I am.” You may contact her at rainbowalisha72 at gmail.com.

References:

American Psychiatric Association, & American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR (4th ed., text revision.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association. (See pp. 291 & 820 for definitions of dissociation; p. 292 for criteria for diagnosis of DID); p. 294 regarding DID and childhood trauma.)

Barlow, M. R., & Freyd, J. J. (2009). Adaptive Dissociation: Information Processing and Response to Betrayal. In P. F. Dell & J. A. O’Neil (Eds.), Dissociation and the dissociative disorders : DSM-V and beyond. New York: Routledge. (See p. 95 for mention of dissociation as a separation of clusters of information in the mind.)

Brand, B., Classen, C., Lanins, R., Loewenstein, R., McNary, S., Pain, C., & Putnam, F. (2009). A naturalistic study of dissociative identity disorder and dissociative disorder not otherwise specified patients treated by community clinicians. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 1(2), 153 – 171.

Chu, J. A. (2011). The memory wars: The nature of traumatic memories of childhood abuse. In Rebuilding shattered lives: treating complex PTSD and dissociative disorders (2nd ed., pp. 78–108). Hoboken, N.J: John Wiley & Sons.

Davidson, R. J., & Begley, S. (2013). The emotional life of your brain: how its unique patterns affect the way you think, feel, and live—and how you can change them. New York: Plume.

Dell, P. F. (2006). _A New Model of Dissociative Identity Disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 29(1), 1 – 26.

Greenspan, S. I. (1997). Developmentally based psychotherapy. Madison, Conn., USA: International Universities Press.

Howell, E. F. (2011). Understanding and treating dissociative identity disorder: a relational approach. New York: Routledge. (See p. xvii-xviii regarding non-familial sources of trauma in childhood.)

International Society for the Study of Dissociation. (2004). Guidelines for the Evaluation and Treatment of Dissociative Symptoms in Children and Adolescents. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 5(3), 119–150. doi:10.1300/J229v05n03_09

Kaplan, H. I., Sadock, B. J., & Grebb, J. A. (1994). Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavorial sciences, clinical psychiatry (7th ed.). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

Putnam, F. W. (1997). Dissociation in children and adolescents: a developmental perspective. New York: Guilford Press. (See p. 13, and from chapter 8 on regarding “discrete behavioral states” in children.)

Ross, C. A., & Halpern, N. (2009). Trauma model therapy: a treatment approach for trauma, dissociation and complex comorbidity. Richardson, Tex.: Manitou Communications Inc.

Shapiro, F., & Forrest, M. S. (2004). EMDR : the breakthrough “eye movement” therapy for overcoming anxiety, stress, and trauma. New York; Oxford: BasicBooks ; Oxford Publicity Partnership.

Siegel, D. J. (2012). The developing mind : how relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. New York: Guilford Press. (See p. 190 for a discussion of psychological trauma.)

Van der Hart, O., Nijenhuis, E. R. S., & Steele, K. (2006). The haunted self: structural dissociation and the treatment of chronic traumatization. New York: W.W. Norton. (The major book-length source on structural dissociation. See p. 9 regarding memory intrusions as partially separated parts of self in PTSD, etc.)

Thanks for this informative article on dissociative identity disorder, trauma-based disorders are relatively common but the strong link to abuse means they are often not discussed due to the sense of shame many people feel.

Can you correct this? Tom Cloyd is not a licensed psychologist, he is a licensed mental health counselor, and currently unable to practice until his license is transferred from Washington state to Utah. Unfortunately this means he can’t treat Trauma or Dissociative Disorders. His license is LH00006462 according to his other website http://sleightmind.com/about-contact/

Psychologists have a higher level of training – to PhD level rather than just at Masters level (which Counsellors have). Coaches are not licensed or regulated so far as I am aware, which is why they can’t treat long term issues such as mental disorders.

Thank you for bringing this to my attention.

I’ve removed the reference “psychologist” from the introduction.