Do you sometimes wonder how much personal information to share with a client? Or whether to disclose any information at all?

The truth of the matter is that we are always disclosing things about ourselves all the time in the way we dress, talk and respond to things that are being shared with us, as well as in how we decorate our offices and more.

To help you navigate the tricky waves of communication, this post will be providing you with some of the key take-aways from Janine Roberts, Ed.D.’s talk about “Therapist Self-Disclosure” at the Psychotherapy Symposium 2013.

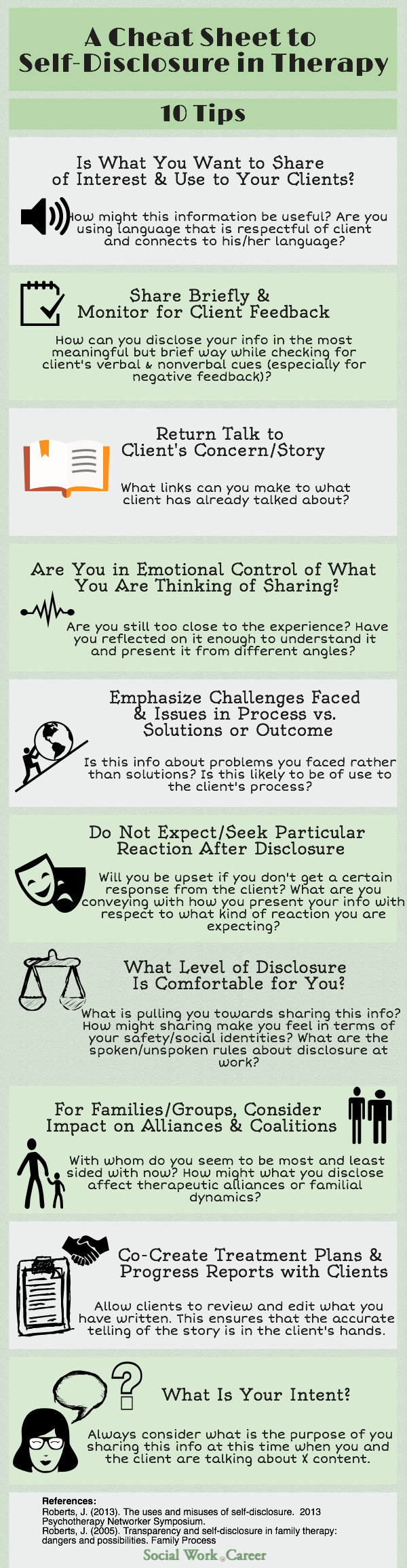

Below is an infographic that summarizes Roberts’ key guidelines about self-disclosure for mental health professionals.

Some good questions for consideration:

What did you learn in the family that you grew up in and/or your family of origin about private/public boundaries and disclosing information about yourself and/or your family?

How was what you learned influenced by your social identities and/or familial social identities such as gender, class, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, culture etc.?

How does what you learned about privacy and sharing inform your thinking and ideas around transparency [sharing of information about your conceptual models, ways of working, values & beliefs and life experience] in your work with clients?

Research has shown that up to 30% of the variability in therapy outcomes is dependent upon the quality and nature of therapeutic relationship, not the specific model or method employed. In Roberts’ emphasis of the importance of the therapeutic alliance, she stresses the value of therapists’ skillful disclosures.

She states that research has shown that clients consistently rate therapists’ skillful disclosures as useful and provided examples of when she has asked clients who’ve been in therapy what was most helpful about their treatment, they typically describe the times when their therapists have shared something about their own personal struggles.

While skillful self-disclosures are of great value, they may also backfire by making clients feel that they need to take care of the therapist or that the therapist isn’t there for them.

To illustrate, Roberts shared a colleague’s case example in which her colleague was working with a woman who had been sexually abused by her father. The client, after a year of treatment, was still blaming herself for the abuse and experiencing difficulties in intimacy with her husband and unable to tell him what her father had done.

After consultation with her supervisor, the therapist disclosed to the client that she had been sexually abused by her father and this was part of the reason she chose to be a therapist. She also shared the part of her journey in which she mastered her shame and guilt.

How did this impact the therapy treatment? On the one hand, this disclosure helped the client let go of some of her feelings and share more with her husband. On the other hand, it made the client feel protective of the therapist and worried about saying things that would be hard for her to hear or give her flashbacks.

From then on, the therapist worked with the client to reassure her that she didn’t need to take care of her and she made an extra effort to monitor her own affect and to check in frequently with her client in this regard.

This case example demonstrates that even when you have thought through a particular situation, consulted with a colleague/supervisor on the matter, be emotionally prepared and share your personal information in the “optimal” manner, the disclosure may still have unintended effects and require thereafter special handling.

In sum, the art of self-disclosure in therapy is much more than thinking through and/or applying Roberts’ guidelines [listed in the above infographic] but in subsequently monitoring and being attuned to your client following the disclosure so as to ensure that your client reap only benefits and not harm from the self-disclosure.

What are your thoughts about self-disclosure? Do you have an example of some information that you have shared which you felt that was helpful [or not]?

Hi Dorlee,

Helpful post! I would like to add a trauma therapy perspective. When I am working with clients with a history of child abuse or neglect, they cannot trust me if they can’t read my positive intentions, so I encourage clients to check out their assumptions about what I am thinking and feeling. I also make every effort to be as authentic and transparent as possible about my emotional reactions, while remaining constructive and therapeutic. This type of disclosure helps clients with impaired trust to learn to distinguish between the intent of my behavior and that of their abusers.

I have also found that sharing briefly about overcoming my own trauma history, without details, can help give clients hope that they can heal. I have used this kind of self-disclosure to resolve therapeutic impasses, especially when a client views suicide as a viable escape from intolerable emotional pain.

All the best,

Andrea

Andrea,

Thanks so much for adding the critical trauma informed lens to self-disclosure. Your type of sharing sounds to me like a more cautious one that encourages a therapeutic alliance, shows the client that he/she is not alone and moves a client out of being temporarily stuck – yet minimizes the risk illustrated in Roberts’ example in which the client started feeling like she had to care for the therapist.

In fact, a part of me wonders whether that therapist who had self-disclosed her trauma had in fact processed it, as well as she thought she had, for the client to suddenly feel/worry about what she might say going forward about her own abuse.

Thanks again for describing your approach. I think your trauma-informed variation takes care of both the therapist and the client but most importantly, the client. The client’s needs are assuredly held front and center [our whole raison d’etre].

Best,

Dorlee

Proper self-disclosure is definitely an art! That’s definitely a great post you have here.

Thanks – Yes, it can be a bit tricky at times to decide what and how much to share.

Thanks so much, Dorlee, for writing this post! I’ll be sharing it with my new supervisee and in my FB group, too. I especially like the 3 questions for consideration that you included here.

One of my own litmus tests for whether or not to share is “Is this fully resolved?” If strong feelings (positive or negative still come up), then it’s not time to share.

Tamara,

Thanks so much for your kind feedback! I’m so glad that you find it helpful to share with supervisees and colleagues 🙂

I also love your valuable added test: “Is this fully resolved?” and totally agree that if the issue is not, this is an indication that it would be prudent to avoid sharing and continue working

on that particular concern.

Thanks again!