How to Help Communities Recover From Disasters

Have you wanted to find out how you may employ your clinical skills to help individuals/the community outside of the traditional setting?

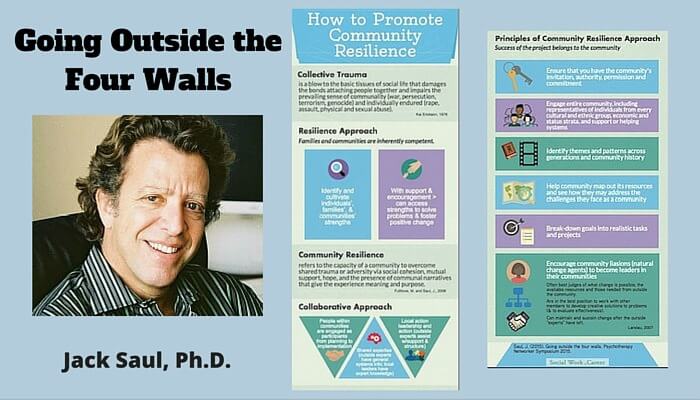

As per the inspiring talk “Outside the Four Walls,” Jack Saul, PhD gave at the 2015 Psychotherapy Networker Symposium, there are many different ways that mental health professionals and social workers may play an important role in non-therapeutic environments, post disaster and post war.

These may include guiding a particular group on how to start up their own non-profit organization, lobbying for better housing laws (when it is the major cause of stress leading to individuals’ mental health problems), listening and helping a collective share their story and thereby heal, or other activities that support a particular community’s needs while building upon its inherent collective strengths.

Individual vs. Collective Trauma

In Dr Saul’s talk, he differentiates between individual and collective trauma.

Individual trauma refers to:

“A blow to the psyche that breaks through one’s defenses so suddenly and with such brutal force that one cannot react to it effectively, leading people to withdraw into themselves, feeling numbed, afraid, vulnerable, and very alone (rape, assault, physical and sexual abuse).” (Kai Erickson, 1976)

Collective trauma, on the other hand, is:

“A blow to the basic tissues of social life that damages the bonds attaching people together and impairs the prevailing sense of communality (war, persecution, terrorism, genocide) and individually endured (rape, assault, physical and sexual abuse).” (Kai Erickson, 1976)

Trauma is not something that just affects us individually, but our relational networks.

Collective Resilience

When people go through very difficult traumas, they are more likely to recover when they are living in supportive and validating communities. This is because more and more research is showing that it is the social environment that people find themselves in after traumatic events take place that may be the key factor in determining how people are going to function and heal afterwards.

Two Questions to Consider When working with a Community Post Disaster:

- What are the capacities that it can shore up to deal with the problems that people in their communities are facing?

- What are the methodologies that we can use to engage these communities and promote this kind of change?

Please see the graphic below for the key take-aways to promote collective/community resilience.

Dr Saul also brought this concept very much to life with a few case examples.

A Few Case Examples:

One example: In 1995, Dr Saul had started a clinic for torture survivors, most of whom were asylum seekers from many different countries who were coming in for evaluations to support their political asylum. They typically came from countries where there was no mental health except for those with only very severe problems. This meant that for the torture survivors, the idea of therapy was something foreign.

When working with this severely traumatized (and now displaced) population, he started to listen to their needs instead of assuming they needed individual therapy. A Tibetan psychiatric resident at Bellevue planned a support group for all those from Tibet. It was very successful, but soon the resident got into conflict with the administration at Bellevue hospital because they wanted all the members to have some sort of diagnosis and go for therapy.

This is not what the members wanted; they liked the fact that they were supporting one another and later they asked Dr Saul to help them form their own nonprofit organization to create a refugee support program to help their community adjust to NYC. He has since learned that the best way for Tibetans to cope is by helping others. Prosocial altruistic behavior is what they consider one of the greatest sources of resilience in dealing with adversity.

Second example: Later Dr Saul was asked to help train U.S. immigration officers to work with individuals who are seeking asylum, but freeze upon questioning (because they may look like they’re faking to the staff). They hired a theatre company to enroll people from different cultures to play people who have been tortured from the different cultures to show how different behaviors and emotions might manifest. They did “stop and go” role plays with the actors. Dr Saul and his team also explained vicarious trauma reactions and provided guidance to the staff on how to take care of themselves.

Third example: After the theatre company did this work with the U.S. immigration officers, they said they wanted to make a play about this issue of refugee and human rights violations in New York to tell the story of the people who are coming into the clinic.

To do so, the professional actors listened to the stories of torture survivors and then they would create scenes. Some of the scenes were verbatim dialogues or monologues and others were embodied performance. The way these actors would interview these torture survivors was totally different from clinicians, although there were some clinicians present to take care of the survivors and the actors if needed. The clinicians wanted to create a safe space for both the actors who were listening and the survivors who were sharing their stories.

The artists would ask: What are the stories that you have to share that have universal importance? This was very different kind of interviewing than a clinical interview. Many of the survivors were already thinking about how to represent this artistically. They were creating something out of their story; i.e., taking a different stance toward their experience which was something horrible, an extremely disempowering experience. This was a way of gaining some power in that story, turning it into something artistically meaningful that can be helpful to others.

The group of actors would bring back the stories back to the survivors to get their feedback. The survivors would say you portrayed the pain and the suffering in the prison extremely well, but now we’re remembering another set of stories of how we survived in the prison by developing these coded languages by knocking on the wall to keep in touch with each other. Or the support we gave each other that allowed us to maintain our sense of dignity and sanity in that context.

The actors’ [practice] performances would elicit more stories of resilience, even to the point of humorous stories with the torturers. These are things which we would never think of asking a torturer survivor. But these were some of the ways, the survivors maintained the sense of humanity of the torturer (protective nature of against being really traumatized). Being tortured is so dehumanizing. The process of healing for many people who have been victimized is seeing the perpetrator as a human also – who were caught somehow in the system.

The actors performed play a few months later. The Chileans opened communication about this with their children for the first time (they hadn’t gone to therapy) but dealing with their trauma on the collective public level was ok. This was a way of expressing responsibility to the people who were left behind.

They wanted people in the U.S. to know what they had been through. When the performance happened, their children wanted to come and read poetry they had written to their parents in this process. The fact that their parents had been involved in this play had led to communication opening up between parents and children about what had happened. This led to similar theatre work being conducted in Chile, which in turn, facilitated more connections. About 15 years later, they had a reunion in which they shared how this drama work had been tremendously helpful to them. A few of them had gone to therapy afterwards; all of them said it saved their marriages.

Dr Saul shared also described working on a torture prevention project in Sri Lanka in Nepal and a resilience project for NYC school community following 9/11. He describes many more cases in his book Collective Trauma, Collective Healing: Promoting Community Resilience in the Aftermath of Disaster.

I found learning about this very social work type of approach to recognizing and validating the inner strengths of a community and working with the different systems/communities from a non-social worker to be wonderful and inspiring.

What are your thoughts about Dr Saul’s collective resilience approach to coping with trauma?

Like this post? Please share it!