Workplace violence prevention is a topic of great interest to social workers and mental health clinicians. This is because health care workers are more likely than workers overall to be assaulted at work, as per the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO, 2016). The most common types of assaults are hitting, kicking and beating and the primary perpetrators of nonfatal violence against healthcare workers are patients in their care, followed by the patient’s relatives and visitors. The full extent of the problem, however, is unknown due to differences in criteria used to record cases, underreporting by healthcare workers and employer inaccuracies in reporting cases.

Workplace violence prevention is a topic of great interest to social workers and mental health clinicians. This is because health care workers are more likely than workers overall to be assaulted at work, as per the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO, 2016). The most common types of assaults are hitting, kicking and beating and the primary perpetrators of nonfatal violence against healthcare workers are patients in their care, followed by the patient’s relatives and visitors. The full extent of the problem, however, is unknown due to differences in criteria used to record cases, underreporting by healthcare workers and employer inaccuracies in reporting cases.

Today, we have the honor of Felix P. Nater, CSC, a Certified Security Consultant, and John D. Byrnes, CEO and lead Instructor at the Center for Aggression Management to provide social workers and mental health professionals with valuable guidance on workplace violence prevention.

Felix helps clients manage & implement workplace security strategy; he has over 20 years of specialized experience & expertise acquired as a U.S. postal inspector and violence prevention and response consultant. John received an honorary doctorate of humanities in 2000 for his development of Aggression Management and provided Insider Threat Prevention Training for the US Army Special Operations Command, Terrorism Division in 2016.

So without further ado, could you provide us with a bit of your background?

Felix: My introduction to workplace violence prevention was through a series of circumstances starting with my role as a United States Postal Inspector on an External Crime Unit in the New York Division in the mid-1970s to late 1980s. The postal service experienced incidents ranging from armed robberies and homicides to the infamous day on August 20, 1986 when Letter Carrier Patrick Henry Sherrill entered the Edmonton Post Office, Edmonton, Oklahoma and shot and killed 20 co-workers before ending his life. Sherrill, a Marine Veteran, had personal issues that conflicted with his ability to cope/manage his life, and resorted to his extreme actions.

Prior to this horrific event, the Postal Service had never experienced such a catastrophic event. This incident sent the United States Postal Service into a frenzy. From the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, there was a rash of workplace homicides at post offices around the U.S. that resulted in the term “going postal.”

Prior to workplace homicides, my contact with workplace related violence was when employees were assaulted and killed during armed robberies. Following those incidents, we were required to develop crime prevention tips to minimize risk to such violence.

On August 20, 1986, I was the public information officer at U.S. Postal Inspection Service, Washington, DC when the Robert Sherrill incident calls started coming in from the media and our senior managers. Prior to the Sherrill shootings, the Postal Service had experienced about 4 employee related shooting incidents between 1975 and 1986. At this point, workplace violence prevention became my passion.

Little did I know that my past experiences as an External Crimes Inspector and my operational and leadership roles in the Army Reserves would be instrumental in developing strategies and tactical approaches to workplace violence prevention.

Following the Edmonton Post Office Shooting in 1986, the Postal Service experienced about 13 workplace related shootings between December 1988 and 1997, and I retired in January 2001. From August 1993 to December 2000, I worked in the field in New York Division as a Workplace Violence Prevention Specialist on the Violence Interdiction Team. We handled hundreds of incidents until my retirement.

By coincidence, my first incident involved a disgruntled letter carrier Vietnam Vet at the Rosedale Postal Station, New York. The decision to establish my workplace security consulting practice came from a call from the Long Island District Human Resource Director following September 11, 2001 who invited me to conduct a workplace security assessment of 125 post offices on Long Island, New York.

John: I’m a businessman, author and lecturer who became interested in the subject of aggression management after concluding that there were no comprehensive training programs dedicated to preventing aggression in the workplace. Due to my research revealing that conventional approaches to deal with conflict and violence were not working, I created the Center for Aggression Management® in 1993 to fill this void and provide organizations with the much-needed Aggression Management® Skills.

How would you define “workplace violence” and “workplace violence prevention?”

Both employer and employees have responsibilities in providing for safe workplaces and personal safety. While there are currently no specific OSHA (Occupational Safety & Health Administration) standards for workplace violence prevention, OSHA has shown initiative and enforcement under the General Duty Clause, Section 5(a)(1) of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970.

The Act states that employers are required to provide their employees with a place of employment that is “free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious harm.” The courts have interpreted OSHA’s general duty clause to mean that an employer has a legal obligation to provide a workplace free of conditions or activities that either the employer or industry recognizes as hazardous and that cause, or are likely to cause, death or serious physical harm to employees when there is a feasible method to abate the hazard.

An employer that has experienced acts of workplace violence, or becomes aware of threats, intimidation, or other indicators showing that the potential for violence in the workplace exists, would be on notice of the risk of workplace violence and should implement a workplace violence prevention program combined with engineering controls, administrative controls, and training.

Therefore, the foundation for the definition of workplace violence is derived from the OSHA Regulation that addresses violence in 4 distinct categories. Preventing workplace violence requires an understanding of what it is in order to implement a comprehensive policy and plan.

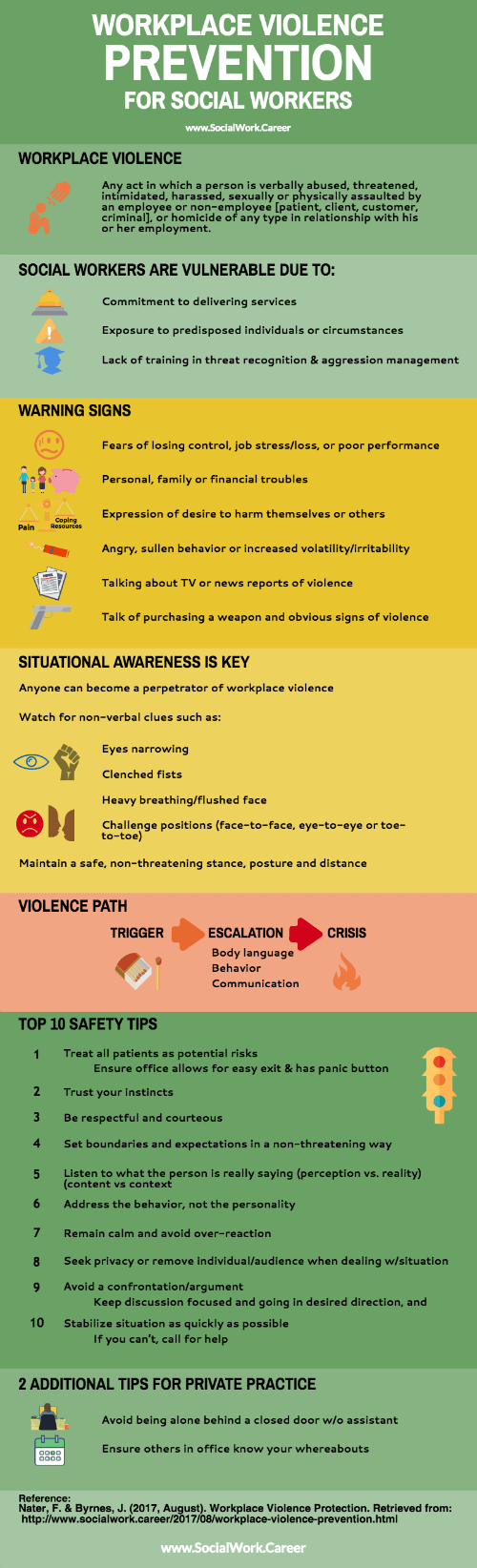

Most workplaces think of violence as a physical assault or the act of homicidal violence. However, it is a much broader problem. It is any act in which a person is verbally abused, threatened, intimidated, harassed, sexually or physically assaulted by an employee or non-employee [patient, client, customer, criminal], or homicide of any type in relationship with his or her employment.

Threatening behavior can include shaking fists, taunting with an object or confrontation, blocking passage or impeding movement, destroying property.

Harassment is any behavior that attempts to demean, embarrass, humiliate, annoy, or cause alarm like verbal abuse.

Verbal abuse includes words, gestures, intimidation, and bullying, inappropriate conduct/activities such as swearing, insults and condescending language.

We talk about employer responsibility under the OSHA to provide for a safe workplace. But what about the employee responsibility? The employee’s responsibility is where being proactive will increase risk mitigation and crime prevention. Being cognizant of your workplace specific security threats can enhance worker safety and security.

So whether mental health professionals and social workers engage with patients and clients in a workplace setting, a remote office or at the client’s home minimizing risk is the employee’s responsibility. The employer’s responsibility to provide quality job specific training also requires that the employee take advantage of the training.

Mental health professionals and social workers seem to be particularly vulnerable to incidents of workplace violence. Why is that?

Mental health professionals and social workers are especially vulnerable because of their commitment to delivering services and their exposure to predisposed individuals or circumstances that increase their exposure and risks. In many incidents, these professionals are not properly prepared or trained on workplace violence prevention, and what constitutes workplace violence.

Perpetrators of violence are typically unknown to the employee unless there is documentation of the known predisposition. Perpetrators can be non-violent patients who become aggressive, as well as known criminals receiving care.

Usually providers work alone, are preoccupied or unsuspecting of their surroundings, work with acute and chronically-ill mental, unstable or volatile persons, work in isolated or low traffic areas, and work in community based settings. The main controlling reasons for such risks are concern with primary duties, and lack of training in threat recognition and aggression management.

Mental health professionals and social workers tend to be employees of lesser positions or authority, newly hired, and uninformed or unaware of policy or procedures. Typically, employees are caught by surprise because of their approach and/or position, perceptions, and understaffing.

The decrease in medical and mental care for mentally ill and patients’ right to refuse medication may also contribute to the increased risk faced by mental health professionals.

What are some red flags for behaviors of disgruntled employees and dissatisfied clients?

Warning signs are subjective, but properly trained employees can quickly assess the warning signs through observation.

Potential warning signs can include: verbalized fears of losing control, job stress, job loss, or poor performance, personal, family or financial troubles, expressions of volatility, expression of doing harm to themselves or others, angry brooding or sullen behavior, increased irritability such as verbal outbursts, employee disputes, feelings of powerlessness, lack of responsiveness from others.

Incidental signs might be frequent calls to friends and family, broken appointments, talking about TV or news reports of violence, talk of purchasing a weapon and obvious signs of violence.

Physical signs might include reading the eyes: a direct, uninterrupted stare to attempt to establish dominance, eyes quickly jerking up and down or from side to side, hallucinating, hearing voices, paranoia (being followed by a non-existent person), and the “target glance” where they look at what they are going to go or do next (will look at your groin before they kick you there).

What are “continuum acts” and how might they correlate with workplace acts of violence?

First of all, anyone can become a perpetrator of workplace violence so situational awareness is essential.

In assessing workplace related incidents of violence, I have found a lapse of judgment based on assumptions, convenience and expediency to be the three prime reasons why victims became victims of violence.

Situational awareness is particularly important when “working alone” or in small groups. Exercising personal safety and security protective measures are imperative in minimizing risks. Examples of risky “assumptions” include “assuming” you can address a patient issue alone, enter a client apartment with unknown others, and that no one is noting when you place your laptop in your car trunk at a client’s residence.

“Convenience” refers to cutting corners because you are in a hurry. For instance, when you’re in a rush to get to the office and unobservant, you may run blindly into an elevator instead of walking up the stairs. This, in turn, may lead you to be met by a robber as the elevator door closes.

With “expediency,” you rationalize that your assumption(s) or doing something for your convenience will pan out. So instead of following protocols, you cut corners by skipping a step. For instance, when runing late for an appointment, you may leave your valuables in your locked car in plain view rather than storing them in your trunk before your arrival.

Perpetrators do not always have a particular relationship and could be bystanders in the area, waiting room, home or other location. Having control of one’s environment is a critical.

“Continuum acts” emanating from aggression behavior typically range from name calling, taunts, threats, shoving, pushing, kicking, to shoving and punching.

Being unsuspecting and unprepared can cause the employee minor or serious injury, if not paying attention. Watch for non-verbal clues to potential escalation to physical violence such as eyes narrowing, clenched fists, increase in respiration, flushed face, face-to-face, eye-to-eye or toe-to-toe are all challenge positions, body posture, proximity and movement can escalate the potential for physical violence.

Maintain a safe, non-threatening stance, posture and distance. Use available barriers when confronted with violence to minimize risk such as counters, desks, chairs and file cabinets. Pay attention to what he/she is wearing and carrying; what they carry can be used against you as a weapon.

What is the significance of primal vs. cognitive aggression?

This research is the product of my associate John Byrne, Center for Aggression Management. Primal and cognitive aggression refer to two types of behavior. Primal is adrenaline-driven aggression and Cognitive is intent-driven aggression.

Twenty-three years ago, the Center for Aggression Management discovered the Primal and Cognitive Aggression Continua. When we brought these two types of aggression together, all of the body language, behavior and communication indicators that we have known about since the beginning of human history fell into place and became empirical. Seven years ago, we were able to scientifically validate these indicators at Eastern Kentucky University.

The real value is that you can now use “objective measurable observables” instead of subjective references like “scary, strange, weird and menacing.” Because we assess only “Aggressive Behavior” and judge it on its merits, we fall outside of HIPAA and Privacy regulations.

How does aggression vary during the trigger, escalation and crisis phases?

The Primal and Cognitive Aggression Continua is further divided by trigger, escalation and crisis phases; these indicators represent someone “on the path to violence.”

The Trigger Phase are little explosions that go off in our heads, like getting up late, going in for coffee and breakfast and finding none, etc. The key is that we “cope.”

When a person stops coping, when one trigger begins mounting on top of another trigger, we enter the Escalation Phase and mounting anxiety. Mounting anxiety changes are body language, behavior and communications indicators that we can identify and measure.

We can use these indicators to determine whether someone is aggressing and at what level of aggression they are. The Crisis Phase is when things become quite dangerous!

What are the nine stages of cognitive aggression that may be used to promote workplace violence prevention (or prevent the escalation/crisis stage)?

Below is an example of the nine stages of cognitive aggression that could easily have been prevented at one of the early stages of aggressive behavior!

Stage One: Sam, an individual who works with you, begins a subtle almost unnoticeable change in his behavior. Normally he is a productive member of your team, cooperative and caring, today, he seems less so. In fact, he has become noticeably distant, uncooperative and nonproductive. When you ask him about this change in behavior, he appears a little scattered and replies, out of character, with something that seems on-its-face to be untrue.

Stage Two: Later that day, you engage Sam in a conversation that evolves into a discussion of office politics. Sam, with a feigned smile, expresses to you that he has a real disdain and negative bias for any “woman boss.” He has become fixated on harming her reputation; he seems to be questioning her effectiveness and trustworthiness.

Sam has worked for this hospital for over twenty-years and was passed over for the promotion to her position. As Sam shares these insights with you, his face becomes flushed with a micro-expression of contempt, so as to further affirm this anguish over having to report to a woman. He angrily proclaims that this hospital passed over him and gave the departmental head job to her only because she was a woman!

Stage Three: A few days later, Sam’s behavior has not improved. In fact, he appears more detached and self-absorbed. Typically, you as a team, guided by your department head, discuss key issues and make decisions collectively about your desired outcomes and strategies to achieve these outcomes.

Sam seems to be acting independently, regardless of any position, you as a team might make. As he acts out, displaying his intent, he seems to be quite fidgety, squirming in his chair and you notice a bead of sweat on his brow.

Stage Four: The following week, one of the other members of the team and a longtime friend of Sam’s, shared with you that he read an alarming message that Sam had posted on his Facebook page. This message questioned the trustworthiness of the department head and whether team members should continue to follow her lead. Sam is also trying to quietly convince other members of your team that “the department head” needs to be taken down a peg or two.

Stage Five: It’s been two months and Sam, who is quite charismatic, has covertly convinced more than half of the dozen team members to his way of thinking. In meetings, Sam has respectfully told the “department head” that many of those here are unhappy with her direction. But when challenged by the department head to be more specific and share his suggestions, he looks at his co-conspirators and with feigned smile, he quietly retreats.

Stage Six: It’s been a month and Sam has exhibited this same behavior a half-dozen times, each time making an accusation followed by a retraction when confronted.

Sam covertly sends a thinly veiled threat to his department head, suggesting that he knows where she lives. One of the department head’s neighbors says that she saw a man’s car meeting Sam’s description parked down the street from her home. The department head figures out who sent the threat, connecting this fact with the alleged stalking and Sam’s employment is terminated with the hospital, predicated on a zero tolerance for making a threat.

Stage Seven: Sam has a few staunch allies within the hospital (within and outside of the team); he has convinced them to keep an eye on the department head, as to where she is and when. With their help, he places an anonymous sealed envelope on her desk containing a picture of her home and a threat to blow it up after she and her family have gone to sleep.

At the subsequent inquest, one of the department head’s neighbors noticed his car again parked in the neighborhood taking photos of her house. Upon further reflection of local law enforcement and review of community traffic cameras, Sam’s vehicle has been seen in his department head’s neighborhood many times over the past two weeks.

Stage Eight: According to family members, Sam is beside himself almost to the point of rage. He has reconnoitered (surveilled) his former department head’s home to determine when she might be home with her family. It is his intention to attack with “shock and awe.”

“These poor people will not know what hit them!” was a statement allegedly made by Sam to one of his friends, who said that this kind of a statement was completely out of character for Sam; and thus, he did not believe a word of it! According to Sam’s friend, this was just Sam blowing off steam after being terminated.

Stage Nine: The day of the intended incident, Sam sees one of his department head’s daughters playing in their yard and decides that he won’t kill them all, only his department head. Sam was an explosives expert in the Army so he decides that he will carry an explosive device on his person, carry it into the hospital and blow himself up with her and anyone else in blast range. He felt that if he was going to give up his life, “I might as well make it a spectacular event; I will be the talk of the Nation’s media for weeks.”

Discussion:

Unhappy patients, clients and disgruntled co-workers take out their frustration in very unique ways, simply because they have access to you and the workplaces. Employers must recognize their duty to create credible reporting that can instill trust and confidence in management’s ability to provide for a safe and secure workplace. That said, employees also have a responsibility not to rationalize and justify their lack of security, safety and vulnerability, by assuming nobody cares or is listening.

When it appears that “nobody” cares, individuals must exercise a greater sense of personal safety and security by reducing risk. Do not intentionally remain in at-risk situations because of duty and obligation over your personal safety. Report the risk factors. Remove yourself from the risk, before there is escalation into physical violence.

What is the connection between acts of defiance by angry patients, clients or disgruntled employees customers and visitors and the threat of violence in the aftermath? We are told by professionals that we must “connect the dots!” But this is too often a question asked in retrospect; this is an after effect accounting, not prevention! If we are to prevent violent and non-violent activities, we must foresee the precursors (get out in front of violence and non-violent acts,) if we actually want to prevent violent or non-violent behavior.

OSHA Guidelines to Preventing Workplace Violence

How might an organization use the 9 stages of cognitive aggression to minimize escalation?

Applying the 9 stages of cognitive aggression means not waiting for an act of aggression before taking reactionary measures but to intervene as hastily and appropriately as possible. Engage at risk individuals as early in the process as possible to avert a crisis.

A conscious thoughtful decision by trained personnel can preempt the escalating stages through proper intervention strategy. Waiting to intervene, or failing to intervene, takes the behavior to a threat assessment phase which is not “prevention” and the “crisis” phase which is managing the aftermath.

Failure to manage the behaviors can result in the potential for extreme justification and rationalization by a disgruntled person. In essence, failure to appropriately recognize how the nine stages of cognitive aggression relate might be the difference between escalation, and swift intervention and employee perception that someone cares.

In his book “In Search of the Miraculous,” Russian philosopher Peter Ouspensky wrote about four basic causes of negative emotions: (1) justification, (2) identification,(3) inward considering and (4) blame. Workplace violence prevention is creatd by applying the nine stages of cognitive aggression combined with early intervention and program management.

While each organization must customize its own violence prevention program, what are 10 best practices to implement in managing potentially threatening behavior?

While best practices are relative, the human element is an unknown factor that responds to the situation based on information, awareness, training, emotions and fear. There may not be time to turn and run. We must recognize that our safety is predicated on our response.

First and foremost, I recommend the recognition of Essential Skills, Qualities and Abilities for De-escalating Situations. One must have the ability to size up the situation quickly, manage situations under pressure, use sound judgment, recognize imminent problems, confront problem situations with confidence, engage individuals to defuse and/or resolve issues, know what and what not to say, react in the face of danger and respond to aggression.

When talking about de-escalation and anger management, my top 10 general best practices are:

(1)Treat all patients as potential risks. Ensure office furniture is properly aligned to allow for easy exit and panic button is installed,

(2) Trust your instincts,

(3) Be respectful and courteous,

(4) Set boundaries and expectations in a non-threatening way,

(5) Listen to what the person is really saying (perception vs. reality) (content vs context),

(6) Address the behavior, not the personality,

(7) Remain calm and avoid over reaction,

(8)Seek privacy or remove the individual/audience when dealing with situations,

(9) Avoid a confrontation/argument. Keep the discussion focused and going in the direction that you want it headed, and

(10) Stabilize the situation as quickly as possible. If you can’t, call for help.

How would your top ten best workplace violence prevention practices differ for a therapist with a private practice?

Only slightly. I would modify the above as follows:

Avoid being alone behind a closed door without an assistant, and

Coordinate care with others in office to ensure they know your whereabouts.

What type of workplace violence prevention trainings do you recommend for agencies?

I recommend audience specific and problem-centered training that includes employee input such as:

• Applying multiple strategies and tactics in controlling at risk situations

• Recognizing Risk Factors to minimize risks in avoiding incidents

• Learning Fundamental approaches to insure personal safety

• Controlling the situation by controlling one’s attitude and behavior

• Minimizing conflict by effective communications

• Responding to aggression with controlled measures

• Dealing with violent incidents

Workplace Violence Prevention Strategies might include audience specific training that supports the strategies for supervisors on managing aggression and dealing with violent incidents in resolving specific problems, supervisor intervention in responding to complaints and observations, reporting and monitoring, assessing and evaluating incidents, defusing conflict and communications.

Lastly, what workplace violence prevention advice would you give new social workers?

Beginning social workers have unique challenges whether working alone or within organizations. The most important advice I can give is not to take things for granted. In fact, the risks are higher for those who develop their own niches. They must find their way.

Workplace and business security are not topics discussed as part of the core curriculum; therefore, it behooves the new practice to start thinking about workplace security and personal safety. Do not assume; consider safety and security over convenience and expediency.

Become familiar with risk factors to minimize risks in avoiding surprises, learn fundamental approaches to ensure personal safety, control the situation by controlling one’s attitude and behavior, minimize conflict by effective communications and respond to aggression with controlled measures.

First and foremost, design your office setting with safety and security in mind. Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED), consider entrances, doors, windows, reception area, barriers, office and examination and waiting areas. In addition, consider access control, visitor management and alarms and panic buttons.

You’ll always have to be security conscious, not paranoid but aware of your surroundings. Always lock the doors leading to the offices or examination areas. Keep all doors leading to the employee areas locked.

Thanks so much for sharing some of your expertise on workplace violence prevention, Felix and John!

U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2016, March). GAO-16-11 Workplace safety and health: Additional efforts needed to help healthcare workers from workplace violence.

It is comforting to know that the employer has a legal obligation to provide a safe work environment. With increased violence in the world, a prevention plan needs to be put into place. It is good to know that the law is helping to make working conditions safe.

This is very good information Dorlee, thanks.

In my career, I have had several clients behave in aggressive ways through taunts or verbal abuse. Fortunately, I was always able to de-escalate possible violence by being patient and listening, but then taking action by prompting the person to come with me to a safer part of the facility, then bidding him or her so long, and letting them know that we will try to work out things when they calmed down. There was only once or twice that I’ve had to stand up and ask a client to leave.