Would you like to know why talking therapy is insufficient for successful trauma treatment of your clients? Or, would you like to be able to improve your results with clients with a history of trauma?

Would you like to know why talking therapy is insufficient for successful trauma treatment of your clients? Or, would you like to be able to improve your results with clients with a history of trauma?

Dr. Bessel van der Kolk, a world-renowned expert on trauma, offers a six-hour presentation on this very topic. In this post, Amy Knitzer, LCSW, shares with you some of her key insights from his “Trauma, Attachment and Neuroscience” training.

A Boston-based psychiatrist, Harvard professor, clinician, researcher, psychopharmacologist, yoga practitioner, and author of the book: The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma, Van der Kolk argues that therapists have been poorly trained, steering clients down paths that won’t yield good results, and offers alternative creative approaches to help individuals heal from their trauma.

Below are some key take-aways:

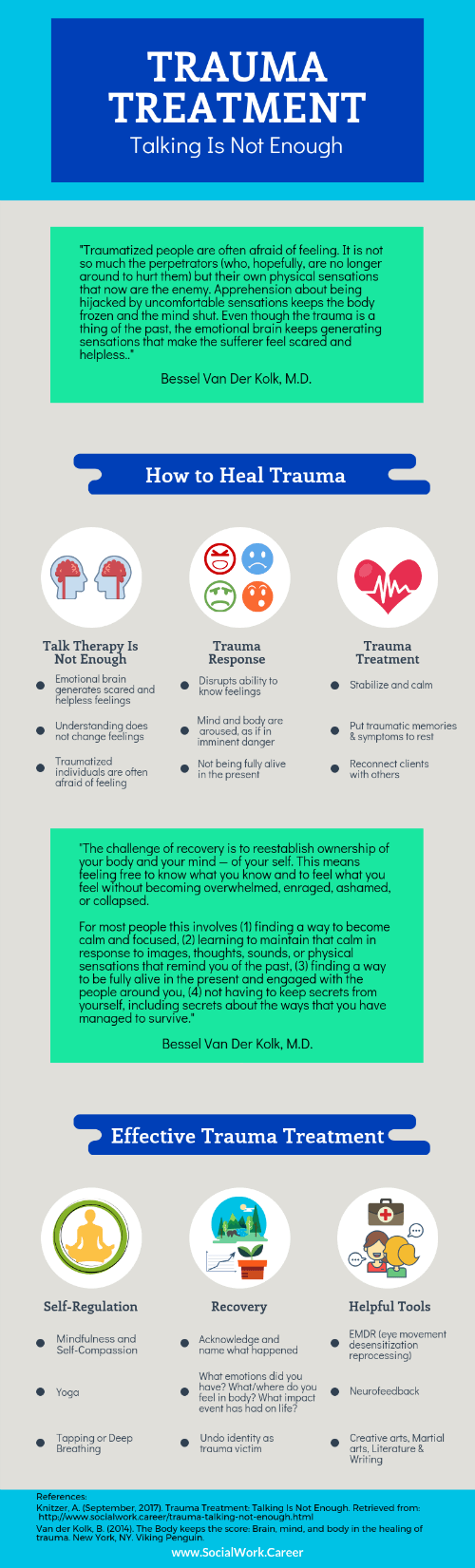

For trauma patients entering a therapist’s office, the trauma is over, because the event ended some time in the past. It does not need to be dug up and divulged in detail to the therapist. “It is none of our business,” Van der Kolk says at one point. He claims, “telling the story” is not helpful.

The therapist must recognize that it is “the imprint the trauma leaves behind and how it changes the brain, perceptions and thoughts,” that must be addressed.

We must learn to help the patient ultimately access the part of the body in which the trauma is lodged–where the body remembers the incident. We must allow them to observe this, and integrate it, so it will lose its power over their lives. This is a complicated process, which he shines light on throughout the lecture.

As an example, Van der Kolk showed a 2-minute clip of a traumatized veteran shopping in a small store, and noted his dazed expression, how hard it seemed for the man to pay attention, and how he misunderstood events around him because he was lost in the memories of war. The man antagonized people and told a small girl to stop crying because “you have no reason to cry. I’ve seen people on fire…” Van der Kolk concludes that when you are this traumatized, “You are no longer alive to be dealing fully with the present.”

He disagrees with what we are taught as therapists, “by talking to people, they will get better.” It is all about skills. Talk therapy and exposure therapy may be somewhat helpful, but his studies do not show patients making significant progress.

The more treatment approaches the therapist can add to her toolbox, the better, he explains. Some people require tapping, deep breathing or other exercises just to establish enough trust to allow the process to begin.

Van der Kolk shares how understanding and feeling are located in different parts of the brain. People may understand their trauma, but their feelings need to emerge in treatment to get results.This is why just talking, and reviewing events, does not seem to help people very much.

He uses Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) often, and recommends helping victims call to mind what they saw, smelled, felt, and heard, and what they were thinking at the time of the event–often incest, rape, violence, war, abuse or neglect. They can keep this all to themselves while you coach them through this tough process of using the senses to remember the event.

The counselor can check in with “How bad is it now?” but not, “Tell me what happened then…” Part of what you are going after is “helping trauma victims remember how they survived the trauma” using EMDR.“ They (the adult patient) need to observe what happened to them (as children).” It is this clear observation that can liberate them.

After perhaps 8 sessions or more of EMDR, the patient will be ready to tell the story. It should come at the end of treatment, not in the beginning according to van der Kolk.

At this point, the patient’s mannerisms will be different– they will be sitting in a more relaxed way. The story will be told in a more casual, talky way. When the patient says “It’s over. I’m done,” and the therapist sees these improvements, he advises ending treatment.

Below is a video clip of Dr. Rick Hanson’s interview w/Dr. Van der Kolk addressing some of these topics.

In Van der Kolk’s presentation, he branches far and wide, from studies of kids who were removed from their London families during WWII, to 9/11 survivors, to people who have suffered multiple traumas, notably abuse, neglect and incest.

He discussed the September 11th attack on the World Trade Centers in NYC, and concluded that people who witnessed the trauma largely did well, in part because the city sent the right message to its residents, to help them stay calm and to offer them help.

He shared a story of a little boy who was in kindergarten class nearby and saw the attack. The boy later drew a picture of people falling off the buildings but landing on trampolines.

It is the quality of having imagination that helped this boy cope, and helps many adults cope with trauma.

During a horrific event, a person is often frozen; powerless and incapable of moving or of changing the outcome. When traumatized individuals are given a chance to use their imagination later, something is released that helps them move beyond the trauma.

Van der Kolk is open to learning from people. When survivors of 9/11 were asked what helped them, acupuncture came up first, followed by massage, yoga and EMDR. He set to learn some of these techniques afterword.

While witnessing a trauma, you put your body in motion if you can. You run or scream or try to get away. The stress hormones help you at that time, to do something. Sometimes you are frozen and cannot act–there is nothing you can do to affect the outcome.

One key part of EMDR is that it gives patients a chance to do something.

Martial arts groups may also be helpful to some trauma survivors. There are some groups like Model Mugging that allow victims to learn self-defense skills, which are then used to fight off an attacker during a planned exercise in class. Students graduate and often shed part of their identities as victims and feel strong.

On a technical level, Van der Kolk explains that when we are exposed to danger, and the brain is in high arousal, the frontal lobe shuts down and the limbic system, the emotional part of the brain takes over.

This is what we see in some people in nursing homes, Holocaust survivors, and some veterans. Many had good lives, but “the stuff starts coming back when the frontal lobe can no longer hold the stuff down.” They are then ruled by the limbic system. Deprived of earlier, effective intervention, the limbic system sets out to destroy all in its path.

Van der Kolk became fascinated with what could help people “so they could balance the pre-frontal lobe and the limbic system.” Kindergarten teachers are his heroes and models because they deal with limbic system breakdown all day, as they witness meltdowns, fights, crying, etc. Teachers intervene with stories, bubbles, hugs, games, physical contact, etc.

Van der Kolk is all about re-wiring the brain, so “life isn’t a repetition of trauma.” His mission is to discover exactly how we can do this.

There is a twin issue of identity that co-exists after trauma. People define themselves as “trauma victims,” “addicts,” or as “incest survivors.” Talk therapies can inadvertently reinforce this message.

There is also neuroscience of identity. Whatever is familiar, sticks. You must do something new to un-wire this association.

The army is brilliant at changing people’s identity. They work the young men and women hard, have them do drills, chant, and live together. By exposing individuals to stress, the army helps their recruits develop new identities. They instill “power, agency, and cohesion.”

He suggests that therapists borrow from the army’s model to find ways to successfully help people change and undo their identity as a trauma victims.

Besides EMDR, Yoga, tapping, and limbic system ideas he is working on, Van der Kolk believes in mindfulness combined with self-compassion.

He spoke of a female patient who as a very young girl was sold by her Dad to men for sex. Over the years, she had turned to great literature as an escape. Often the stories had an empowered person in them. Eventually, in treatment, she shared other fantasies and escapes.

While listening, the therapist acted in a neutral way, encouraging her to go on–but not cheering–as she healed herself. The part of her that was frozen was taking action to undo the power of the event.

Deep breathing also changes the heart rate variability, so that the mind becomes clearer. “You want people in a medium arousal state, from which they can process stuff.”

Van der Kolk is very sensitive to the plight of young children who have only their caretakers. If there is abuse or neglect, there is nothing these children can do. Adults can take a drink, or a pill, or deal with tragedy or pain actively, but children are defenseless.

Overwhelming affect states lead often to cutting, drugs or alcohol in later life, and those are the brunt of the adults Van der Kolk’s team treats. Unfortunately, “not feeling safe as a child was a predictor of not responding to therapy,” further complicating the treatment.

Other topics discussed include attachment theory and what happens when children didn’t have anyone they felt safe with while growing up. His specialty was in discussing the brain, what goes awry in those during early trauma, adult trauma and multiple trauma. To learn more, take Van der Kolk’s training on Pesi, or read his wonderful book The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma.

Like this post? Please share it!

About the author: Amy Knitzer, LCSW is a social worker with many years of experience working with inner-city children and families. Currently, she is counseling and running support groups for elderly residents, as well as for survivors of suicide loss. In addition, she acts with the New Jersey Mental Health Players, a troupe that reenacts mental health issues for audiences and helps de-stigmatize mental illness.

so true, trauma does not need to be retold but processed. and new skills learned.

Patients tell us group therapies where other vets tell trauma stories are not helpful to them because recovery from PTSD requires more than retelling.

In addition, being confronted when feeling are overwhelming is not therapeutic and I believe patients need to feel safe in general thus I tell them to walk away if they feel overwhelmed.

Being afraid with severe anxiety is dangerous and I prefer patients to not be in the situation.

I tell them to walk away and find a safe place where they can relax and calm down. Think about pleasant things and do some relaxation exercises. Patients have told me sometimes others refuse to let them leave when something is upsetting them. Humans need more compassion for innocent trauma survivors and be sensitive to their needs. There is no need to insist they must disclose details that are private. Thanks for a nice wakeup.

Hi Dr. Wagner,

Thanks for your response and the sensitivity and options you describe that you afford your patients.

Dr. van der Kolk is refreshing, particularly when he tells us that getting the details of a trauma is none of our business. I guess it’s a fine line at times, figuring out who benefits from re-telling about the trauma and who does better just recalling it and keeping silent. But it is nice to hear a psychiatrist who is so confident that the work can get done without the patient having to speak of the traumatic event.

I like your approach and the idea of compassion for people who have already suffered. Yes, we need more common sense compassion.

Thanks!